Position Statement

Ensuring Equity for Youth by Addressing the Intersectionality of Gender, Race, and SexualitySocial and ecological conditions must be addressed in order for members of historically marginalized populations to achieve justice and equitable health and well-being outcomes.

Adopted by

the Healthy Teen Network Board of Directors on

September 21, 2017

Position

Healthy Teen Network believes that addressing social and ecological conditions unique to members of historically marginalized populations (such as people who are women, First Nation/Indigenous, African-American, Latinx, Asian Pacific Islander, and/or LGBTQ+) is critical for these populations to achieve justice and equitable health and well-being outcomes.

We call for individuals and organizations practicing in the health field to deepen their understanding of and pay greater attention to the contextual realities of historically marginalized populations.

Healthy Teen Network believes and research supports1 2 that to better serve members of historically marginalized populations, health service providers must acknowledge the residual impacts of various social toxins which legitimized and institutionalized discrimination against these populations. Providers must understand how ongoing social toxins such as misogyny, racism, heterosexism, homophobia, and transphobia are linked to health disparities for these populations. Providers must develop culturally responsive and culturally affirming practices and environments, so members of historically marginalized populations can feel safe and supported throughout the entire continuum of care process. Health service providers should develop and be supported in their development of new knowledge, skills, mindsets, and behaviors that allow them to effectively and authentically engage and serve members of historically marginalized populations.

Issue

The health field has traditionally relied on disease prevention models and individual behavior frameworks that assume equal opportunity is available to all humans and that following medical advice and/or engaging in healthy behaviors is an individual choice. These approaches tend to use blaming language for persons who “fail to comply” with treatment or cannot sustain a behavior change because these approaches do not recognize the impact of social and environmental factors that influence behavior. Disease prevention approaches are particularly unfit for addressing the needs of historically marginalized populations as a result of the over-emphasis on individual behaviors and failure to give adequate attention to the context in which people live, play, and work.3

Disease prevention approaches are particularly unfit for addressing the needs of historically marginalized populations as a result of the over-emphasis on individual behaviors and failure to give adequate attention to the context in which people live, play, and work.

Supporting Information

The term “intersectionality” refers to overlapping or intersecting social identities—such as but not limited to gender, race, and sexuality—and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination—such as misogyny, racism, and patriarchy.4

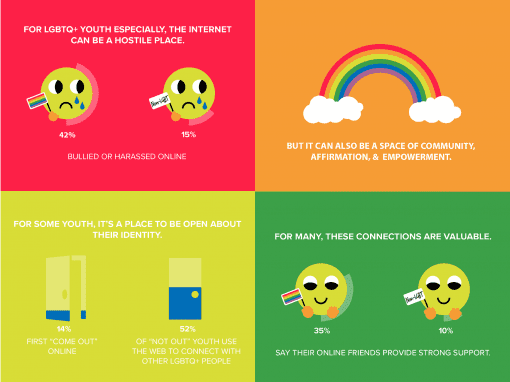

Historically marginalized populations have higher rates of health disparities and negative sexual health outcomes, which are attributable in part to structural inequalities such as racism, heterosexism, and homophobia/transphobia.5 For example, it is projected that one out of two Black gay/bisexual/ men who have sex with men (MSM) and one out of four Latino MSM will become HIV positive during their lifetime.6 First Nations/Indigenous people have the second highest rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea.17 LGBTQ+ youth of color experience violence, bullying, and harassment in greater degrees and have an increased risk of health disparities than their white LGBTQ+ peers.8

Intersectional scholarship has linked these realities to larger historical and contemporary contexts. The issues that impact health equity for historically marginalized populations are complex and require complex solutions generally involving diverse teams of practitioners, substantial community engagement, and a holistic view of health and well-being. Service providers play a pivotal role ensuring that historically marginalized populations achieve positive and lasting health outcomes.

Providers can take action in several different ways:

- Training and capacity building: Providers can deepen their knowledge and skills through capacity-building assistance tailored specifically to address (conscious and unconscious) bias, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and structural inequalities.9 10

- Policy and advocacy: Providers can advocate for local, state, and federal public policies that support and center the needs of historically marginalized populations and allocate resources to those communities.11 12

- Organizational development: Providers can encourage the development of policies and procedures within their organizations that ensure historically marginalized populations have access to high quality, culturally responsive, and affirming, staff, administrators, and various other health professionals throughout the entire continuum of care process. Creating a needs assessment is a critical first step.13 14

2 Brave, H. M. Y. H. (2003). Morning Star Rising: Healing in Native American Communities – The Historical Trauma Response Among Natives and Its Relationship with Substance Abuse: A Lakota Illustration. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 35, 1, 7.

3 McLeroy, K. R. (1989). An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15, 4, 351-77.

4 Williams, Kimberlé Crenshaw. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color”. In: Martha Albertson Fineman, Rixanne Mykitiuk, Eds. The Public Nature of Private Violence. (New York: Routledge, 1994), p. 93-118.

5 Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2010). Disparities.

https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Disparities.

6 Centers for Disease Control (2016). Lifetime Risk of HIV Diagnosis. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2016/croi-press-release-risk.html.

7 Centers for Disease Control (2017). HIV Among American Indians and Alaska Natives In The US.

https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/aian/.

8 GLSEN (2014). Experiences of LGBT Youth of Color. https://www.glsen.org/learn/research/national/report-shared-differences. 9 Center for Whole Communites. http://wholecommunities.org/.

10 See organizations like Undoing Racism: The People’s Institute For Survival and Beyond (http://www.pisab.org/) and Race Forward (https://www.raceforward.org/) for additional capacity building assistance.

11 Health Resources and Services Administration.

https://www.hrsa.gov/about/organization/bureaus/ohe/healthliteracy/resources/index.html.

12 Office of Minority Health. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/.

13 National Prevention Information Network.https://npin.cdc.gov/pages/cultural-competence.

14 National Center for Cultural Competence. https://nccc.georgetown.edu/index.php.