Position Statement

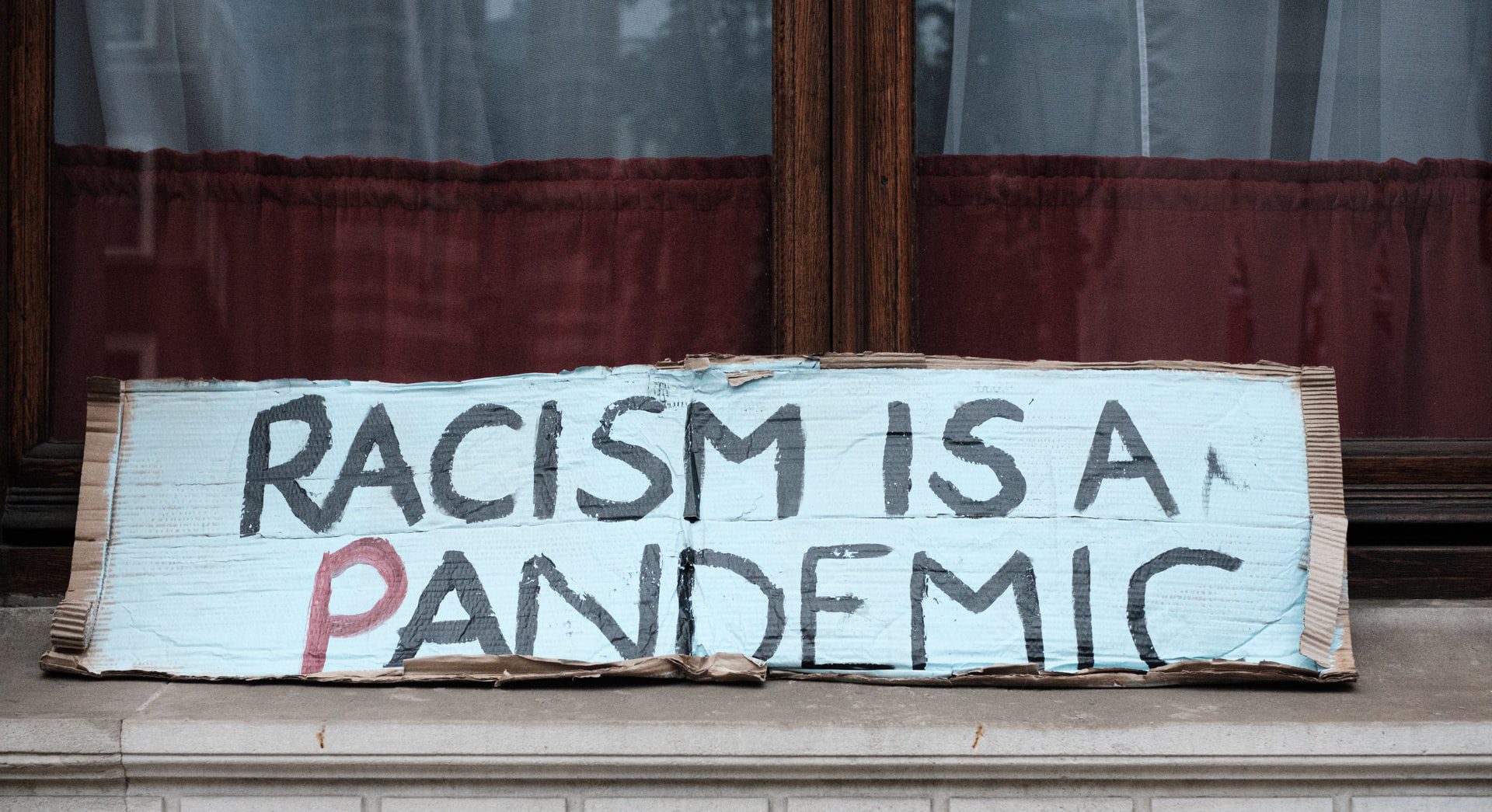

Ensuring Equity by Dismantling RacismRacism within health care must be dismantled to achieve health equity for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

Adopted by

the Healthy Teen Network Board of Directors on

September 21, 2017

Position

Healthy Teen Network believes that racism remains a persistent social toxin within U. S. society. Further, we believe that the ongoing and disparate impacts that racism has on public health at large warrants additional and sustained attention. While we recognize that race is a social construct with no biological basis, the material impact of racial classification based in pseudo-science persists today within health care systems and throughout society.1 Therefore, Healthy Teen Network believes that racism within health care broadly and within the adolescent sexual and reproductive health field specifically must be dismantled to achieve health equity for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

Issue

Health disparities based on race within the U.S. are well documented within the public health field.2 Racism, a system used to interpret human differences and assign economic value and higher social capital to some and lower social and economic value to others, operates in many ways throughout society. Racism operates at the individual level (prejudice and bias attitudes), at the group level (discrimination against entire groups of BIPOC), institutional level (policies, laws, and practices), and at the ideological level (social attitudes and belief systems).3 4 These various levels perpetuate, reinforce, and enable systems of racism to persist. These complex and interconnected systems of oppression plague society and have a documented detrimental impact on mental,5 emotional,6 sexual,7 and physical8 health of BIPOC.9 10 11

Supporting Information

In order to ensure equity for BIPOC, the enduring burden of racism and the contemporary manifestation of systemic racial oppression must be acknowledged and remedied. Front line staff, direct service providers, and administrators all have a critical role to play if BIPOC are to have access to quality health care and sexual and reproductive health services.

Front line staff, direct service providers, and administrators all have a critical role to play if BIPOC are to have access to quality health care and sexual and reproductive health services.

It has been documented that healthcare provider bias can have an impact on the health outcomes of BIPOC.12 One study found that racial microaggressions by health care providers impacted American Indian mental and physical health.13 Another study found that HIV positive Black and Latino men who have sex with men who experienced racial discrimination from health care providers had lower CD4 counts, were less likely to be undetectable, and more likely to visit emergency rooms.14 In these instances, the unconscious beliefs of providers resulted in a material impact on the health and wellbeing of BIPOC.

Providers can take action in several ways to mitigate the impact of racism:

- Organizational development: Organizations can assess the organizational culture and values and determine how, if at all, the organization is advancing racial justice internally and externally as well as social justice broadly. Providers and administrators can work collaboratively to establish institutional policies and practices that ensure equity within its organization (hiring, firing, promotion, performance) for People of Color. Additionally, providers can establish diverse community partnerships, create advisory boards that are representative of the various racial/ethnic groups they serve, as well as institutionalize continuous quality improvement processes that involve diverse racial/ethnic groups being served.

- Capacity building and training: Providers and administrators can deepen their own knowledge and skills through capacity building assistance specifically targeted to explore historical and contemporary manifestations of racism, bias, and racial micro-aggressions in healthcare both at the individual level as well as the systems level.

- Awareness raising: Providers and administrators can work collaboratively to create and establish opportunities within their organizations for employees that acknowledge and celebrate the rich and complicated racial and ethnic history of the United States. Additionally, providers and administrators can create opportunities for open and honest dialogue on the impact of race, racism, white privilege, and white supremacy and its role in shaping American history and organizing social relations. Public policy and advocacy: Providers and administrators can advocate at the local, state, and federal level for public policies that guarantee quality healthcare access for BIPOC who need it. The policies that are being advocated for would be created through a collaborative process that meaningfully engaged Communities of BIPOC.

1 Ford, Chandra L., & Airhihenbuwa, Collins O. (2010). Critical Race Theory, Race Equity, and Public Health: Toward Antiracism Praxis. American Public Health Association.

2 Ryn, M. ., & Fu, S. S. (2003). RACIAL/ETHNIC BIAS AND HEALTH – Paved With Good Intentions: Do Public Health and Human Service Providers Contribute to Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health?. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 2, 248.

3 Griffith, D. M., Johnson, J., Ellis, K. R., & Schulz, A. J. (2010). Cultural context and a critical approach to eliminating health disparities. Ethnicity & Disease, 20, 1, 71-6.

4 Adams, M., Bell, L. A., & Griffin, P. (2016). Teaching for diversity and social justice.

5 Harrell, S. P. (2000). A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70, 1, 42-57.

6 Nadal, K. L., Griffin, K. E., Wong, Y., Hamit, S., & Rasmus, M. (2014). The Impact of Racial Microaggressions on Mental Health: Counseling Implications for Clients of Color. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92, 1, 57-66.

7 Hill, C. P. (2004). Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. New York: Routledge.

8 Anderson, K. F. (2013). Diagnosing Discrimination: Stress from Perceived Racism and the Mental and Physical Health Effects*. Sociological Inquiry, 83, 1, 55-81.

9 APHA Policy Statement 6502: The Health of Minorities and the Relationship of Discrimination Thereto. APHA Public Policy Statements, 1948-present, cumulative. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

10 APHA Policy Statement 7424: Racism in the Health Care Delivery System. APHA Public Policy Statements, 1948-present, cumulative. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association.

11 Noonan, A. S., Velasco-Mondragon, H. E., & Wagner, F. A. (2016). Improving the health of African Americans in the USA: An overdue opportunity for social justice. Public Health Reviews, 37, 1.)

12 Hall, W. J., Chapman, M. V., Lee, K. M., Merino, Y. M., Thomas, T. W., Payne, B. K., Eng, E., … Coyne-Beasley, T. (January 01, 2015). Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 12, 60-76.

13 Walls, M. L., Gonzalez, J., Gladney, T., & Onello, E. (2015). Unconscious biases: racial microaggressions in American Indian health care. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : Jabfm, 28, 2.)

14 Bogart, L. M., Landrine, H., Galvan, F. H., Wagner, G. J., & Klein, D. J. (2013). Perceived Discrimination and Physical Health Among HIV-Positive Black and Latino Men Who Have Sex with Men. Aids and Behavior, 17, 4, 1431-1441.