Position Statement

Sexual & Reproductive Health Services for System-Involved YouthSystem-involved youth deserve comprehensive sex ed and optimal sexual and reproductive health services in order to achieve whole health.

Adopted by

the Healthy Teen Network Board of Directors on

June 9, 2017

Position

Healthy Teen Network believes that youth in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems (system-involved youth) deserve comprehensive sexuality education and optimal sexual and reproductive health services in order to achieve whole health. SRH services should be designed and delivered with consideration for system-involved youth.

Issue

System-involved youth are an extremely vulnerable population with increased risk for unintended pregnancy, HIV, and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).1 System-involved youth have a double vulnerability—adolescence, a critical stage marked by increased risk for negative social and behavioral outcomes—and being in out-of-home care. These youth need many supports to help them as they transition out of care due to a history of inconsistent, disrupted relationships and multiple placements, trauma and other adverse childhood experiences, chronic depression, exposure to domestic and community violence, engagement in high-risk behaviors, and fractured or non-existent support systems.2

System involvement during adolescence provides challenges and barriers additional to those that all adolescents face, especially as it relates to sexual and reproductive health. Without strong social support and family networks, these youth face an increased risk of engaging in risky behaviors, including early sexual debut, unprotected sex, and sex with multiple partners.3 These sexual risk-taking behaviors put youth in danger of acquiring STIs and having an unintended pregnancy.4

Without strong social support and family networks, these youth face an increased risk of engaging in risky behaviors, including early sexual debut, unprotected sex, and sex with multiple partners.

Many system-involved youth exhibit elevated risk-taking behaviors posing a real threat to their well-being. Sexual risk behaviors, more specifically, such as early age of sexual initiation and multiple sex partners,5 pose a serious threat and lead to negative outcomes. Teen girls in out-of-home care report a higher rate of pregnancy than the general population of similar age (33% compared to 19%) and are more likely to have had more than one pregnancy (23% compared to 18%).6 Young mothers in foster care may have unique needs and challenges, including being at increased risk for rapid repeat pregnancies and lacking adequate parenting skills.7 Half of 21-year-old men aging out of foster care report they had fathered a child, compared to 19 percent of their peers not in the system.8

System-involved youth face different barriers to sexual health care compared to their peers in the general population. Foster youth have reported that what sexual health information they do receive is too little too late.9 This may be due to earlier sexual initiation as system-involved youth tend to be sexually active by the time they first receive information about birth control and contraception.10 These youth also cite that they find it challenging to access condoms and general information about sexual health care,11 or they are uncomfortable seeking sexual reproductive health information.12 As a result, despite reductions in teen pregnancy nationwide, system-involved youth’s pregnancy rates remain high, with girls reporting rates up to two times that of their peers.13

System-involved youth could benefit from interventions that could lead to prevention of unintended pregnancies and the incidence of STIs. Currently available evidence-based sexual health interventions are not sufficient to address the needs of this vulnerable population of youth. Many of these programs have multiple sessions that are not suitable for youth in care who are subject to placement turnovers; and these programs provide broadly relevant skill building, which does not account for the unique needs of youth in out-of-home care.14

Supporting Information

There are approximately half a million children and youth in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems in the United States.15 Adolescents comprise half of this population. Youth in out-of-home care may be involved in multiple systems, including child welfare, juvenile justice, mental health care, and special education.

The goal of foster care is to reunify children and youth with their parent or guardian or find another suitable permanent living arrangement, which may include an adoptive home, guardianship, or placement with a relative. For older adolescents, the program may offer education and resources for preparation to transition to independent living as adults. The goal of the juvenile justice system is to punish and rehabilitate youth who have committed a delinquent act.

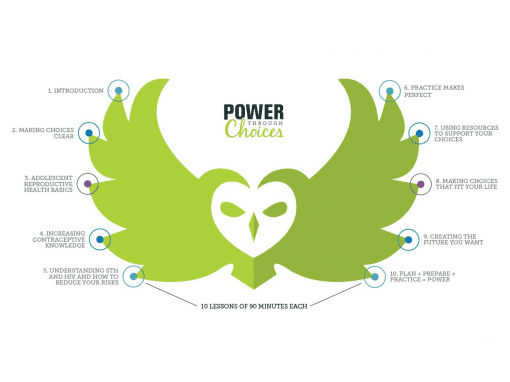

For both systems, their needs often exceed capacity. Systemic issues decrease their youth’s access to sexual health services, increase their barriers to service utilization, and limit information provided to them on their sexual health and development.16However, there is a growing focus among these systems on the adoption of evidence-based practices to address child well-being outcomes, including physical and mental health. Also, interventions intended for system-involved youth are currently being rigorously evaluated, such as Power Through Choices17 and Making Proud Choices for Youth in Out-of-Home Care.18 These programs show promise for engaging system-involved youth and decreasing sexual risk behaviors.

2 Cunningham, M.J., & Diversi, M. (2013). Aging out: Youths’ perspectives on foster care and the transition to independence. Qualitative Social Work, 12(5), 587-602. DOI: 10.1177/1473325012445833

3 Boustani, M.M., Frazier, S.L., & Lesperance, N. (2017). Sexual health programming for vulnerable youth: Improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 375-383. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.013

4 Finigan-Carr, N.M., Murray, K.W., O’Connor, J.M., Rushovich, B.R., Dixon, D.A., & Barth, R.P. (2014). Preventing rapid repeat pregnancy and promoting positive parenting among young mothers in foster care. Social Work in Public Health, 30(1), 1-17. DOI: 10.1080/19371918.2014.938388

5 Boustani, M.M., Frazier, S.L., & Lesperance, N. (2017). Sexual health programming for vulnerable youth: Improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 375-383. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.013

6 Courtney, M., Terao, S., & Bost, N. (2004). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Condition of the youth preparing to leave state care. Chicago, IL: Chaplin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago.

7 Finigan-Carr, N.M., Murray, K.W., O’Connor, J.M., Rushovich, B.R., Dixon, D.A., & Barth, R.P. (2014). Preventing rapid repeat pregnancy and promoting positive parenting among young mothers in foster care. Social Work in Public Health, 30(1), 1-17. DOI: 10.1080/19371918.2014.938388

8 Svoboda, D.V., Shaw, T.V., Barth, R.P., & Bright, C.L. (2012). Pregnancy and parenting among youth in foster care: A review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(5), 867-875. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.023

9 Boustani, M.M., Frazier, S.L., Hartley, C., Meinzer, M., & Hedemann, E.R. (2015). Perceived benefits and proposed solutions for teen pregnancy: Qualitative interviews with youth care workers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(1), 80-92. DOI: 10.1037/ort0000040

10 Love, L.T., McIntosh, J., Rosst, M., & Tertzakian, K. (2005). Fostering hope: Preventing teen pregnancy among youth in foster care. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. Available from https://thenationalcampaign.org/sites/default/files/resource-primary-download/FosteringHope_FINAL.pdf

11 Boustani, M.M., Frazier, S.L., & Lesperance, N. (2017). Sexual health programming for vulnerable youth: Improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 375-383. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.013

12 Hudson, A.L. (2012). Where do youth in foster care receive information about preventing unplanned pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections? Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 27(5), 443-450. DOI: 10.1016/j.pedn.2011.06.003

13 Dworsky, A., & Courtney, M.E. (2010). The risk of teenage pregnancy among transitioning foster youth: Implications for extending state care beyond age 18. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(10), 1351-1356. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.06.002

14 Boustani, M.M., Frazier, S.L., & Lesperance, N. (2017). Sexual health programming for vulnerable youth: Improving knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 375-383. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.01.013

15 USDHHS. (2016). Child Maltreatment 2014. Washington, DC. Available from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment

16 Robertson, R.D. (2013). The invisibility of adolescent sexual development in foster care: Seriously addressing sexually transmitted infections and access to services. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(3), 493-504. DOI: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.12.009

17 Becker, M.G., & Barth, R.P. (2000). Power through choices: The development of a sexuality education curriculum for youths in out-of-home care. Child Welfare, 79(3), 269-282.

18 Jemmott, J.B., III, Jemmott, L.S., & Fong, G.T. (1998). Reductions in HIV risk-associated sexual behaviors among black male adolescents: Effects of an AIDS prevention intervention. American Journal of Public Health, 82(3), 372-377.